|

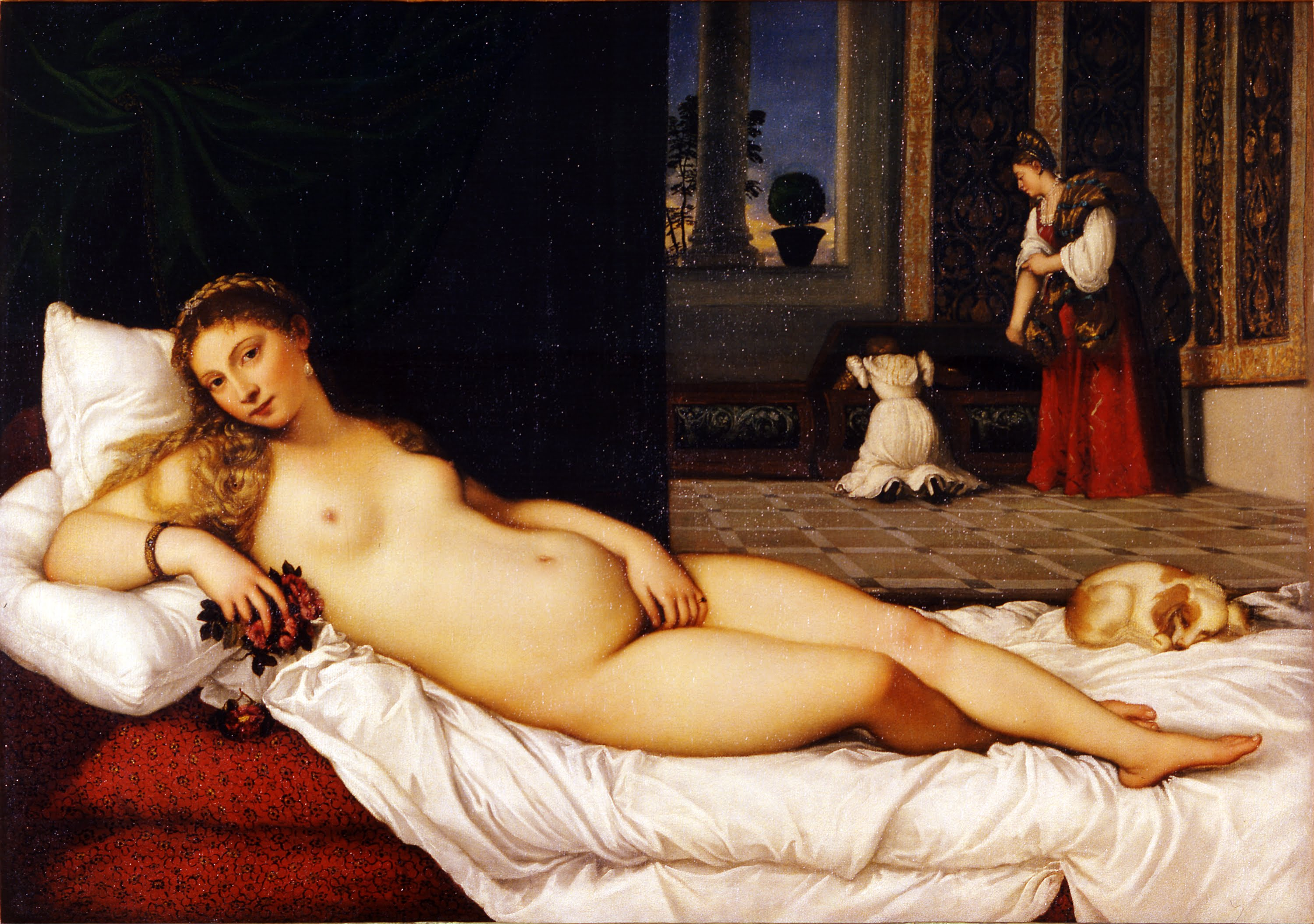

| Titian's Venus of Urbino is a classic example of work made for the male gaze. |

The male gaze as I understand it, is a concept that asserts that in most forms of media, the viewer is automatically assumed to be a heterosexual male, and therefore the images of women presented to them through various mediums are created to appeal to their sexual desires.

In his 1972 BBC television series and book Ways of Seeing, John Berger argues that the male gaze is a long standing tradition which can trace it’s origins back to the European nude painting. He posits that “To be naked is to be oneself. To be nude is to be seen naked by others and yet not recognized for oneself. A naked body has to be seen as an object in order to become a nude.” (Berger 54) It’s precisely this type of objectification, appealing to the sexual desires of men that effectively dehumanizes the women on display. They are no longer people, but rather things to be looked at for the pleasure of the men looking at them. Berger also argues that in this predicates the role of men as the surveyor, stating that men determine how they treat women based on their perceptions of them. And that a woman therefore learns to survey herself constantly, or as Berger puts it, “Her own sense of being in herself is supplanted by a sense of being appreciated as herself by another.” (Berger 46) The author then offers up a provocative simplification of his argument in the phrase “men act and women appear.” (Berger 47)

_08.jpg) |

| Marylin Monroe's appearance in River of No Return (1954) as cited by Laura Mulvey |

Interestingly enough, this “tradition” has been able to make it’s way into modern and contemporary mediums such as film, an argument beautifully outlined in Laura Mulvey’s essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” published only three years after Berger’s work. In the third portion of the text entitled “Woman ad Image, Man as Bearer of the Look,” Mulvey similarly states that “The determining male gaze projects it’s phantasy on to the female figure which is styled accordingly.” (Mulvey 837)

And it is through film that we find the emergence of the oppositional gaze as a construct of of black female subjectivity. Author bell hooks outlines the concept in detail, as part of her book “Black Looks: Race and Representation” in which she moves past a focus on gender representation within the cinema and more closely focuses on the aspect of race. She posits that the “gaze has been and is a site of resistance for colonized black people globally” going on to say that “In resistance struggle, the power of the dominated to asset agency by claiming and cultivating ‘awareness’ politicizes ‘looking’ relations-one learns to look in a certain way in order to resist.” (hooks 116)

Lamenting the racially hostile and stereotyped representations plaguing mainstream cinema, bell hooks calls upon black women to be critical of the films (and by extension, all media) they consume and seek out narratives that “do not simply offer diverse representations, they imagine new transgressive possibilities for the formulation of identity.” (hooks 130)

|

| Just one example of idealized female bodies in comic books. Click here for an interesting article on the male gaze as it appears in DC Comics. |

As an artist/illustrator and avid reader of comic books, my artistic inclinations and sensibilities have been greatly informed by work that caters to the male gaze through their depiction of idealized female body types and traditional notions of feminine beauty. It’s been interesting to see just how unconsciously I have reinforced and catered to the male gaze in my own work and it’s something that I’m trying to work on. In terms of the oppositional gaze, I completely agree with hooks in her assertion that the only way to move past the problematic representations of race and gender in film is to be critical in what we consume. This is the only way to help us move past the “single story” that’s been put forth.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.